Why Millions of Gray Squirrels Crossed America in Swarms

Original article and photos by S.Veigel 01/13/2023

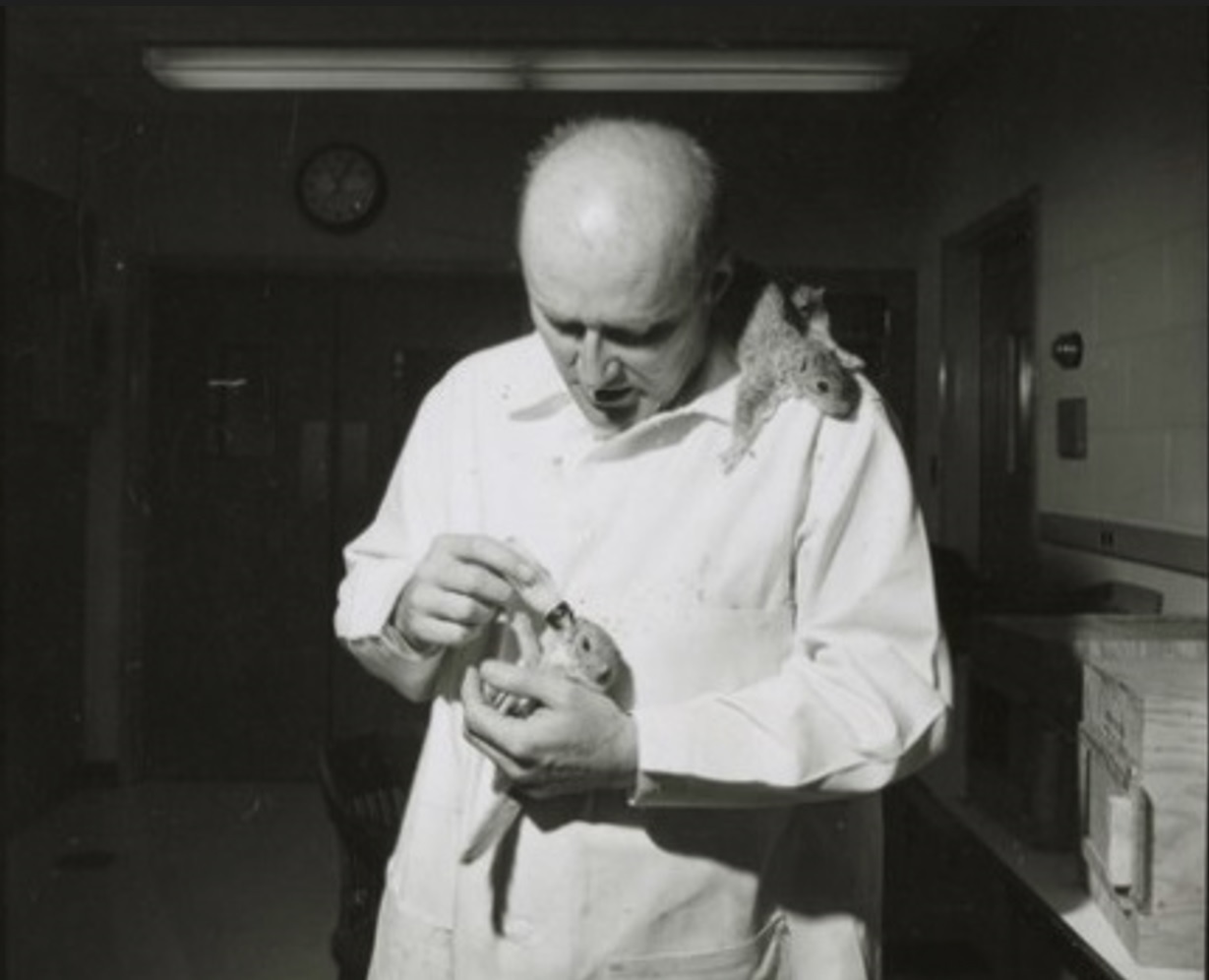

Photo of Dr. Vagn Flyger by permission University of Maryland

I: Massive Gray Squirrel Emigrations

For 219 years of U.S. history people spoke of, wrote papers on and published newspaper articles concerning “mass squirrel migrations” (better understood as emigrations). Throughout the 1800’s newspaper reports of active “migrations” were published, on average, once every 5.25 years (depending on the region of the country). By the 1900’s the average time between reported occurrences was 17.75 years and newspaper articles were more about historic occurrences; with a 35-year spread between the last reported occurrence in 1933 and the events of 1968. The question to be answered here is, “WHY?”

For 219 years of U.S. history people spoke of, wrote papers on and published newspaper articles concerning “mass squirrel migrations” (better understood as emigrations). Throughout the 1800’s newspaper reports of active “migrations” were published, on average, once every 5.25 years (depending on the region of the country). By the 1900’s the average time between reported occurrences was 17.75 years and newspaper articles were more about historic occurrences; with a 35-year spread between the last reported occurrence in 1933 and the events of 1968. The question to be answered here is, “WHY?”

Ia: Context

Depending on who was reporting on these mass squirrel emigrations, and where they were occurring, the number of squirrels all moving in herd-like (or stampede) fashion was anywhere between 3,000 and half a billion. People might describe 30,000, millions or just “innumerable”. But no matter how many were reported and where they were, these were massive numbers everyone took notice of.

On October 8, 1884 The Somerset herald in Pennsylvania published the following article. It read in part, “… Thursday and Friday thousands of squirrels had crossed the Monongahela a short distance above that town and took a northeasterly direction.” “… The relator (a witness interviewed) stated that in 1859 he had witnessed a much more extended migration of squirrels at Blennerhasset Island, near Parkersburg at the mouth of the Kanawha. Said he: ‘I saw them coming over in sholes and if I had been in the way they would have suffocated me, so thickly did they run in masses.’”

1885 The Abbeville Press banner, South Carolina

Source: The Library of Congress

On June 20, 1894 The Seattle post-intelligencer in Washington State published the following article. In part it reads, “For the past few years, until the present one, this vicinity has been troubled a great deal from the ravages of this pest (squirrels)”… “…A gentleman recently passed through the St. John country and reports the squirrels out by the millions. The ground seems to move in waves so thick are they.” In another paragraph the article continues, “Very few squirrels are left in this vicinity. The strange bumming tour now in progress will be watched with a deal of interest by the farmers to the west.”

On October 21, 1925 the Grant County Herald in Lancaster Wisconsin published the following article. It read in part, “…they (gray squirrels) are going, thousands of them, across the Mississippi from Wisconsin to Iowa.” “The migration has been going on for six weeks. Lately, however, the squirrels seem to be moving in greater numbers.” “One duck hunter Thursday saw a group of them mid-channel, apparently near drowning from exhaustion.” “… judging from the great numbers that are migrating, most of the squirrels must keep right on traveling after they finish their great swim of the Mississippi.”

By the 1900’s the tone and tenor, even the frequency, of mass squirrel emigrations had changed. On November 20, 1935 The Washington times in Washington D.C. published a story about squirrel emigration. That article reads in part, “…All the stories of the great squirrel migrations of the past say they swam rivers, swarmed through houses and fields, destroying crops, allowing nothing to divert them. But in 1933 they were turned back by rivers, and even by traffic cops. There is a well-authenticated story that 12 of them whisked onto the Yonkers ferryboat, dodging hands, and debarked at Alpine, on the Jersey side; but, on the whole, they were in no such do-or-die mood as their ancestors.”

II: Explanations throughout antiquity

When you experience a preponderance of events, like recurring mass squirrel emigrations, you might be willing to accept any plausible explanation available. These explanations in the past came from old timers, hunters, game wardens and, later from learned men in the early 1900’s. But until 1968 there had never been a coordinated scientific study of these mass emigrations.

Below is a list of the explanations most often reported.

1]: Squirrels were in search of better food. 2]: An increase in flea population agitating the squirrels. 3]: the gray squirrels were driven out by the red squirrels. 4]: Squirrels at the statehouse in Columbus Ohio had invited the influx. 5]: Closing tree cavities with concrete. 6]: Rapid increase and consequent over-crowding. And number 7, the most interesting of all, “sunspots”.

On May 18, 1903 The Vinita daily chieftan of the Cherokee Nation in Oklahoma published an article wherein they quoted Dr. John A. Kennicott. The fact that, throughout history, the emigrating squirrels were passing through areas “when the mast (tree tops) was exceedingly abundant” was not lost on Dr. Kennicott and he offered the following note. “The reason for these migrations is not satisfactorily explained. That they are caused by the want of food is hardly probable, as the squirrels are found to be fat at the time and as often leave localities abounding with food as otherwise.”

III: The nature of the beast

Since before the 1800’s the words used to describe mass squirrel migrations (emigrations) were “unexplained” or “not satisfactorily explained”. But we do know some things about squirrels.

First of all, gray squirrels are individuals. There are squirrels common to an area that other squirrels tolerate, even befriend (they have ways of indicating friendly intent) and they do have relationships. But they are not herd animals. Just because some squirrels are running or chasing each other doesn’t mean the others are going to stop what they’re doing or even look up. If they’re not the female being chased by a male during mating season, they don’t seem to care.

First of all, gray squirrels are individuals. There are squirrels common to an area that other squirrels tolerate, even befriend (they have ways of indicating friendly intent) and they do have relationships. But they are not herd animals. Just because some squirrels are running or chasing each other doesn’t mean the others are going to stop what they’re doing or even look up. If they’re not the female being chased by a male during mating season, they don’t seem to care.

Also, gray squirrels, though they move around individually, are generally content to stay where they are. They do not have migratory urges like birds flying south for the winter, or salmon swimming back upstream to lay eggs every year.

Second of all, unless gray squirrels are foraging and burying food, or looking for a mate, they don’t spend a great deal of time in the grass with the fleas and ground based predators. Gray squirrels prefer to live in trees and travel from tree branch to tree branch (or across objects like fencing). They also live quite comfortably with red squirrels and any other non-threatening species that will give them some personal space.

Third, when it comes to flying predators, or any other predator, gray squirrels have keen sight, other senses and extremely quick reflexes. They are also keenly aware of how the birds are behaving. When any danger is indicated, which they are keenly aware of as a matter of daily life, they take to the nearest tree trunk or branch and flatten out, taking advantage of their dark color as camouflage.

Though predator birds, like hawks, do catch some squirrels off guard it is not normally that easy to fly into a tree and grab an animal, from within the branches, who can take off in any direction. I once saw a hawk bounce off a tree trunk as it swooped in to snatch a squirrel. Within the snap of a finger, that squirrel suddenly darted sideways around the tree trunk and disappeared out from under the hawk’s talons.

Last of all, squirrels can swim, but unless they are forced to, they will not. And no mother squirrel is going to move her babies to a new location unless all hell is breaking lose.

So how do you herd thousands or millions of gray squirrels in one direction? You can’t. There is just no way even the best sheep dog, or any other creature on God’s green earth, could herd one single squirrel. Because they are individuals who can move multi-directionally with quick responses; horizontally or vertically.

So how do you herd thousands or millions of gray squirrels in one direction? You can’t. There is just no way even the best sheep dog, or any other creature on God’s green earth, could herd one single squirrel. Because they are individuals who can move multi-directionally with quick responses; horizontally or vertically.

But is the 200 plus year “I don’t know” answer that really fixed and unsolvable? They don’t migrate naturally. They don’t travel in groups or herds. They hate swimming. They’re not easily chased out by other animals (or fleas). And in every account they’re well fed on their journey. So why did thousands and millions die crossing rivers? And why did some make such a long trek with their babies?

IV: Enter Dr. Vagn Flyger (1968)

The last great squirrel migration

In September of 1968 North Carolina (and elsewhere) was experiencing an unusually large influx of squirrels. Concerned that the squirrels were starving, many concerned citizens were calling for large quantities of nuts to be brought in from as far as Florida. The Smithsonian Institution’s Center for Short-Lived Phenomena picked up on the activity and started making phone calls to biologists, game wardens and, among many, a man by the name of Vagn Flyger.

On October 3, 1968 The Cherokee Scout in Murphy North Carolina published an article which reads in part, “In response to reports of mass starvation and mass migration of gray squirrels, a study was initiated by the North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission.”

The importance of this study is that it was the only broad scale coordinated study of this phenomena in U.S. History.

University of Maryland 1968

By permission University Archives

As part of a large well-coordinated team Dr. Vagn Flyger was the leading expert on squirrels in 1968. He also authored a report, titled “The 1968 Squirrel ‘Migration’ in the Eastern United States”, presented to the Natural Resources Institute at the University of Maryland.

At the time Dr. Vagn Flyger was a distinguished wildlife biologist and a professor emeritus at the University of Maryland. Dr. Flyger had a bachelor’s degree in zoology from Cornell University, a master’s degree in wildlife management from Pennsylvania State University and a doctoral degree in vertebrate ecology from Johns Hopkins University.

I have provided a link to this 1968 report, but for my readers I’d like to mention just a few key points.

1: In the “discussion” section of the 1968 report Dr. Flyger states in part, “Squirrel ‘migrations’ occurred during recent historic times and have been described by Seton (1920) and Schorger (1949). These migrations occurred almost invariably during September.”

2: Dr Flyger continues, “As the forests of eastern North America were cut in the late 1800’s gray squirrel ‘migrations’ became less frequent and on a smaller scale; during the last 100 years they have become relatively rare. The reason why these ‘migrations’ occur especially during the month of September when food conditions are at their best has been puzzling. Squirrel ‘migrations’ occur unannounced, and by the time a biologist arrives on the scene to investigate the situation, the event has usually ended. As far as I know, this is the first ‘migration’ that has received much attention by biologists.”

V: Why nothing solved in 200 years

People, though broadly intelligent, naturally have a narrow focus when it comes to animal behavior. They see animals behaving a certain way and they want to know what’s with that animal. The animal is invading their territory, farms and homes and they just want them gone. They didn’t see gray squirrels as little gardeners of the forest planting trees. They saw them as bushy tailed little rats.

People, though broadly intelligent, naturally have a narrow focus when it comes to animal behavior. They see animals behaving a certain way and they want to know what’s with that animal. The animal is invading their territory, farms and homes and they just want them gone. They didn’t see gray squirrels as little gardeners of the forest planting trees. They saw them as bushy tailed little rats.

On April 2, 1892 The Ohio Democrat in Logan Ohio published an article from Harper’s Magazine that references where we begin with part of the answer. The article reads in part, “Accounts by early writers show that squirrels must formerly have been amazingly numerous.” “… Pennsylvania paid eight thousand pounds in bounties for their scalps during 1749 alone. This meant the destruction of six hundred and forty thousand within a comparatively small district. In the early days of western settlement regular hunts were organized by the inhabitants, who would range the woods in two companies from morning till night…”

VI: So why then gray squirrels? Why September?

You can count the number of animals in the U.S. who store food for the winter on one hand. And the gray squirrel is a master at burying stores of food in the ground. All the gray squirrels emigrating were fat with food because they eat every day, they bury food every day and they must fatten up for the winter. But just because the mast was abundant at the time the squirrels were emigrating doesn’t mean the gray squirrel is going to be assuaged. Because when winter comes, that abundance is not going to be there.

Squirrels bury food near where they live. They need some personal space so each squirrel can hide enough of its own stash to survive the winter without other squirrels finding it and stealing it. During the winter they want to go eat some of what they stored without having to travel very far in freezing weather.

Squirrels bury food near where they live. They need some personal space so each squirrel can hide enough of its own stash to survive the winter without other squirrels finding it and stealing it. During the winter they want to go eat some of what they stored without having to travel very far in freezing weather.

By the 1800’s the timber industry in the Great Lakes region and the northwest was in full swing. Throughout the 1800’s there was no regulation and timber barons viewed the forests as an inexhaustible resource. Nearly half the timber cut wasn’t even used. It was left to rot and no new trees planted. Once a forest had been stripped the land was sold to settlers for farming. In other regions there was mining, industry, towns and cities spreading out, unregulated hunting en masse and war.

During the 1800’s gray squirrels were constantly pushed into smaller areas where thousands of squirrels already had a home creating unnatural competition. But it wasn’t just the squirrels being pushed out. The hawks, the fox and wolves were also being pushed into these areas increasing anxiety among the population. So when winter was approaching squirrels trying to create stores of food were finding their situation untenable.

It didn’t happen all at once, but squirrels naturally started moving looking for somewhere they could spread out, have a home and do what they had been doing for millions of years. But there were just too many. Not enough time to even bury an evening meal. And more predators. Including gun shots.

A hundred squirrels trying to find room to spread out with food to eat. They meet another hundred. Traveling through already highly populated areas. Then there’s a thousand. And then 30,000. Swimming rivers, eating crops to survive on their journey. Just trying to get to open land. Then the swarm spreads out and the “migration” is over.

It’s not that difficult or mysterious. People just don’t include themselves or predators in the study. How they tend to create the thing they fear.

Author’s Observations:

I spent hours per day (starting at 2 a.m.), 365 days a year for two years, observing, photographing and interacting with wild animals coming into my yard to feed. These included possum, rabbits, various birds (including hawks), lizards, tree frogs and squirrels. I observed a baby squirrel coming down to eat at night. I watched an eastern cottontail rabbit build a nest and raise her baby. I read about the animals, then compared what I saw.

References:

Library of Congress (Digital Newspaper Archive Search). Search criteria 1800 thru 1968.

https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/newspapers/

“The 1968 Squirrel Migration” by Vagn Flyger

http://www.myoutbox.net/flyger.htm

“The Texas Gray Squirrel Migration of 1857” by Stanley D. Casto

The Texas Gray Squirrel Migration of 1857 (sfasu.edu)

Photo “Dr. Vagn Flyger feeds squirrels by hand”. By permission 01/31/2023

Special Collections & University Archives, University of Maryland

“Massive squirrel migrations recorded in North America”

Massive squirrel migrations recorded in North America | Farm Progress